And we're off to Millbank

Today we visit Millbank prison on the banks of the Thames in c. 1872 - and some of the women who were incarcerated there

From 1818 to 1890, when it was torn down to create the Tate Gallery, Millbank Penitentiary was home to thousands of prisoners, including, for a few months, the subject of my work in progress, Marguerite Diblanc.

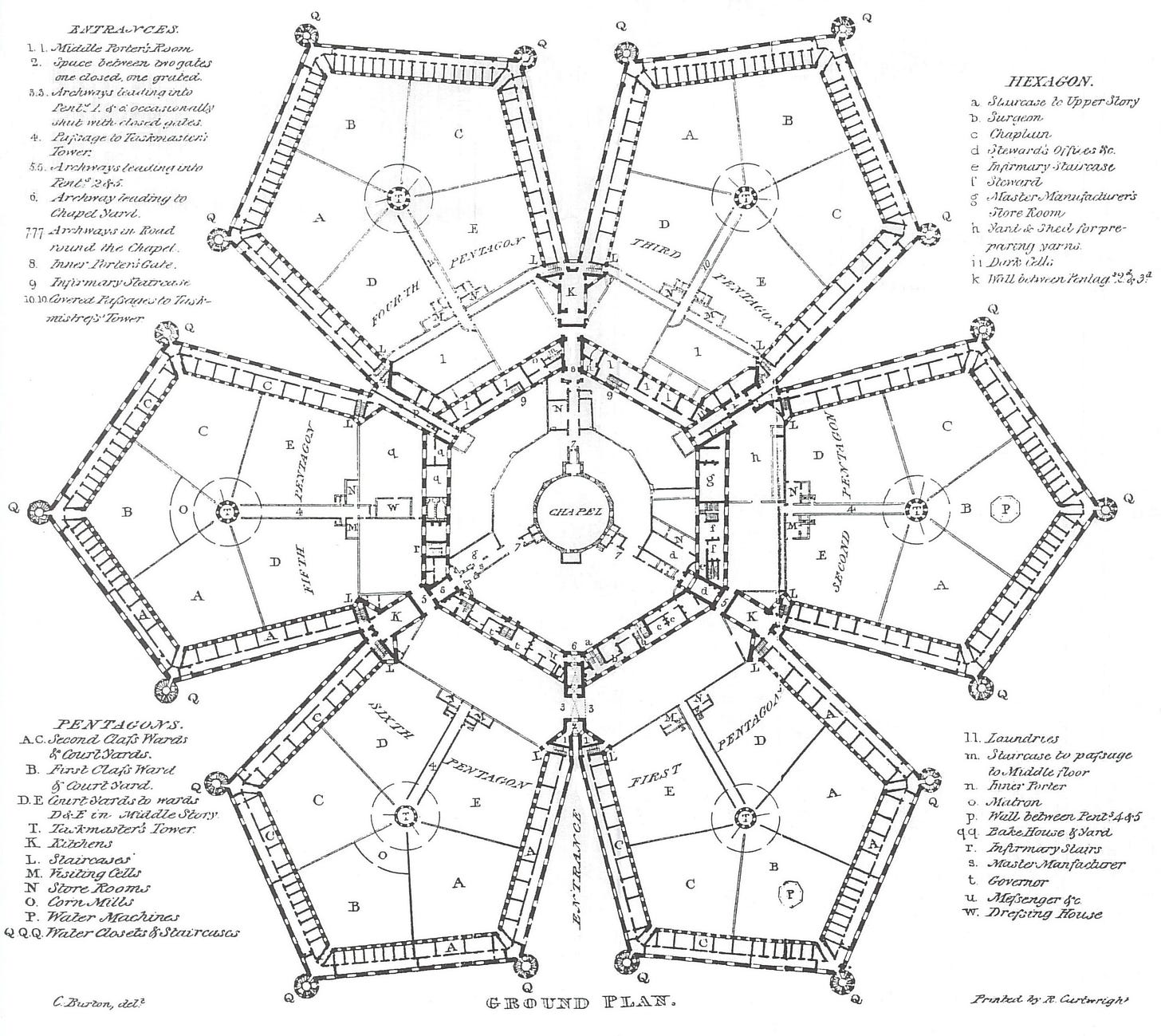

The first thing to understand about Millbank was its highly unusual shape — six petal-shaped pentagons, with three round turrets on the corners from which the officers (the women warders were called matrons) could observe the prisoners in their cells at all times.

The complicated design included numerous corridors (some of them leading to dead ends) and staircases. It was so confusing in places that the staff sometimes left chalk marks on the walls so that they could find their way back to where they started. The whole complex was surrounded by a dank moat, traces of which still remain. The site had been marshland, which contributed to the damp, fetid atmosphere.

My personal feeling is that the odd-angled rooms and spaces and the bad air may have induced or at least promoted an additional sense of unease in the prisoners and the warders.

A London Inheritance is particularly good on the architecture of Millbank.

Millbank was a prison of hard labour, which for men could be anything from the treadmill or crank to working in the kitchens and for women sewing or laundry work. The first few months, however, were spent picking oakum (coir), in silence and in isolation from other prisoners. This involved taking old ships’ ropes, which had been covered in tar, wrapping them around a hook held between the knees and unravelling it with your hands. The resulting strands were re-used to caulk the inside of ships’ hulls. It was very difficult, tough work, extremely hard on the hands. The occupation, and the silence, was meant to focus the prisoner’s mind on the enormity of their crime so that they emerge from the experience truly penitent. This stage of imprisonment was called probation.

One of my tasks while writing the sections in which Marguerite was held at Millbank was to describe the building and the regime without sounding like a history lecture. I was lucky in that I was able to gain inspiration from Sarah Waters’ 1999 novel Affinity (not her best IMHO but nevertheless quite atmospheric), which was made into a TV film in 2008.

Sarah Waters’ research is always thorough. The film-makers included all the elements of the cells at Millbank that were described in Waters’ book and in her original sources, the most descriptive being Henry Mayhew and John Binney’s The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life (1862).

As we peeped into one of the little cells, we saw a good-looking girl with a skein of thread round her neck, seated and busy making a shirt. The mattress and blankets were rolled up into a square bundle, as in the male cells. There was a small wooden stool and little square table with a gas jet just over it; the bright tins, wooden platter, and salt-box, a few books, and a slate, and signal-stick shaped like a harlequin's wand, were all neatly arranged upon the table and shelf in the corner.

When Mayhew and Binney walked around the women’s pentagon (number three) the matrons told them that most of the prisoners were convicted of theft but that those serving long sentences were usually first-time offenders who had committed infanticide.

Mayhew and Binney, being true Victorians, could not pass up the opportunity to comment on the appearance of the women. ‘Some are pretty, and others coarse- featured women; many of them are impudent-looking, and curl their lip, and stare at us as we go by,’ they wrote.

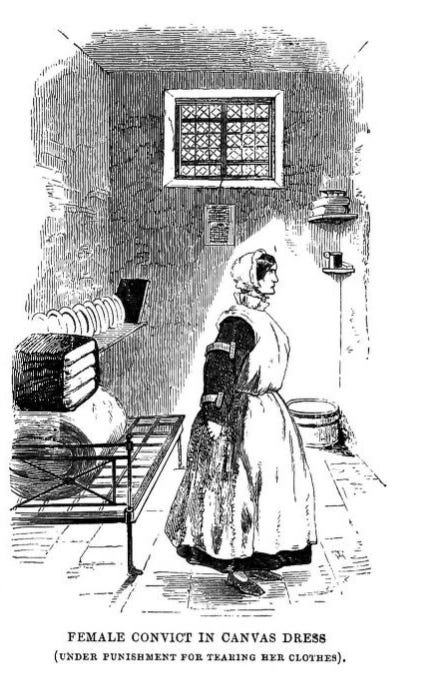

They also visited D ward, passage 2, known as the dark, where women were put as punishment.

Presently we saw, inside one of the cells we passed, a girl in a coarse canvas dress, strapped over her claret-brown convict clothes. This dress was fastened by a belt and straps of the same stuff, and, instead of an ordinary buckle, it was held tight by means of a key acting on a screw attached to the back. The girl had been tearing her clothes, and the coarse canvas dress was put on to prevent her repeating the act.

To gain an idea of the women Marguerite would have joined when she was sent to Millbank, I looked at the 1871 census. This lists 382 women convicts. I put half of them in an Excel spreadsheet and ran them through the Cliffordometer. This rough picture emerged:

The youngest were two 18-year-olds, Elizabeth Cawley from Devon and Sarah Ann Nash from Worcestershire; the oldest was Phoebe Hodges, a glass polisher from Birmingham aged 65. Twenty per cent were born in Ireland. Just over half were married or claimed to be; 11 per cent were widowed. All of those whose occupations were recorded (a third had no occupation) were from what might be called the labouring classes, with the exception of Julia Hart, a bookbinder. There were 17 factory hands; 16 servants; 14 hawkers; 11 laundresses; 8 charwomen; 7 dressmakers; 5 seamstresses; and 3 needlewomen.

The census does not give details of the women’s crimes so I’ve picked out a few to research, with the idea that Marguerite may have met them. I chose women with slightly unusual names purely because they are easier to find in the records.

Harriet Lloyd (aka Davies), a servant, was 25 in 1871. In 1870 she was sentenced at Oswestry, Shropshire to seven years hard labour for larceny (theft), the lengthy sentence because she had previous convictions for the same offence.

Ann Hulston, a 29-year-old servant, was also known as Sarah Parkes. In 1867 she was sentenced to seven years for larceny after a previous conviction. In 1878 she was sent to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum at Crowthorne in Berkshire.

Julia Hart, 23, was a bookbinder from Southwark, south London, who was convicted of uttering counterfeit coin and sentenced to five years hard labour.

I had a glance through the other 181 women (those who were not put through the Cliffordometer), and found two 17-year-olds as well as Agnes Stewart, a 23-year-old governess who was convicted of stealing goods to the value of £6 from her employer,. She had a previous conviction and sometimes went by the name Mary Ann Storey.

Another of the challenges of writing Marguerite’s trial and the Millbank passages (the book is entirely from her point of view) is including dialogue she would not have been able to understand, as she did not, to begin with, speak English. My current draft includes a character based on Maria Kikiller (probably Kigler), 43, a German cook who was convicted at Taunton with her husband of stealing over £200-worth of plate and jewellery from Maria’s employer, and was incarcerated in Millbank at the same time as Marguerite. I am considering having Maria communicate with Marguerite, after she has completed her probation, using words shared between German and Marguerite’s Mechois, a dialect of Flemish.

In early 1873 Marguerite was sent to Woking Women’s Convict Prison in Surrey, which had a very different regime. More on Woking in a later post.

That’s all for now!