London — Jules Vallès detested it all

The weather, the people, the buildings, everything. And he wrote his hatred of the city out in 300 furious pages

What a sinister impression is given by these terraces, eaten away by fog and rain! Those dismal London houses … carry tones of prison or the scaffold.

La rue à Londres, Jules Vallès, 1883.

Jules Vallès was a journalist and left-wing political activist who found refuge in London after the fall of the Commune, the short-lived experiment in socialist government that was brutally extinguished by right-wing republicans in May 1871. At the time — oh my god, it’s almost unbelievable! — there were no border controls and literally anyone could go through customs at Dover and start living in England. He lived in London for about ten years, every minute of which he hated.

Vallès, born into a middle-class family in the Haute-Loire in 1832, was a marked man, even among the refugee community, which was riddled with French government spies and agents provocateurs.

He had long been persecuted by the authorities. When the Commune was established in the wake of the Franco-Prussian war, he published Le cri du peuple, a left-wing newspaper, but that proved a little too much even for the new government, and it was temporarily banned.

The Commune lasted a mere seven weeks. On 21 May 1871, government troops, assisted by the Prussians, punched through the city. It took seven days of bloodshed to bring it to an end. Estimates of dead vary between 5,000 and 30,000. Vallès, who fought in the streets, escaped, and went into hiding in Paris.

Government soldiers thought they had identified him among the thousands of prisoners being marched en bloc to Versailles. Émilie Noro, who was among the captives, recalled the event years later:

A tall young man with a beard and black hair was being dragged by the soldiers. A voice arose from the crowd:

“It's Jules Vallès! It's Jules Vallès! To death!”

I saw him throw his head back, raise an arm and fall, crying: “Long live the Republic!" At the same time, the crackle of twenty rifle shots tore my ears.

Les Temps Nouveau, 18 January 1913

It was the wrong man.

Vallès made it, via Brussels, to London, where he was given a death sentence in absentia for ‘looting, complicity in the murder of hostages and complicity in acts of arson’.

In London he set about making a new life, turning himself into a writer of novels rather than a journalist. The difference was significant as writers were members of the bourgeoisie, part of an elitist literary establishment, whereas journalists were activists. But everything went wrong for him. His fortunes nosedived and he was forced to scrape a living teaching and writing. His relationship with his partner fell apart when he got another woman pregnant and the baby died. He spent time in a workhouse.

He vented his spleen in articles about London published in L’Événement (and elsewhere). These were compiled, after his return to Paris (there was a political amnesty in 1880) and published as La rue à Londres, in 1884, with 22 beautiful etchings by fellow exile Auguste-André Lançon.

La rue à Londres is a volume of so-called “social reporting” in which Vallès explored the slums, workhouses, markets, ports, pubs of London. The text is, in the words of John Sturrock in the London Review of Books, “dreadfully monotonous”; “it was all money-grubbers, ugly women, killjoys of one kind or another, its sole advantage over Paris being the policemen, who weren’t so quick to rough you up.”

Some examples…

On the subject of women:

After they stop being young girls, they are immediately old — with no transition — they are ruined in the blink of an eye, like game birds.

Even the domestic maids come in for scorn:

All are dressed in the same way, in a lilac dress (lilac fried in oil) and crocheted cap which looks like a pinch of sugar, held by a thread on the head.

As for England, it’s

a country of bad living, bad eating, bad sitting, and bad sleeping… ENGLAND HAS A HORROR OF COMFORT!

The workhouse was a form of purgatory worse than Dante's Inferno (fair enough perhaps), where a heartless regime aimed to keep inmates just about alive but not much more, to vindictively separate families, and do pointless forced labour. He wrote of a former schoolteacher but who had lost his job and had come into the workhouse with his wife and frail six-year-old son, who died within a month.

He described the casual ward, which was for specifically for overnight stays. In return for a place to sleep and a hunk of bread he had to pick oakum, that is untwist old tar-bound ropes. Everyone had to do hard labour, “the strong or the weak”. He witnessed a man die on the job.

Vallès was not impressed by London’s markets. He thought Petticoat Lane in Spitalfields a place of almost unmitigated despair and misery. The old clothes for sale were rancid, the dresses, were “soaked with the sweat of twenty women” or smelled of the morgue.

An outside view on yourself or on your favourite place (London, in my case) is always valuable, even one through such an unhappy lens (so to speak). We know London life in the Victorian age was harsh on the have-nots. Vallès had come through the regime of Napoléon III, the siege of Paris, the trauma of the Commune and still found nothing to celebrate in London. I have my doubts. It seems to me that he did not at any point compare and contrast the position of women in France and England (the subject of a future Substack, perhaps), that he was able only to see life through his own narrow experiences.

Vallès died in Paris 1885, aged only 52, from complications arising from diabetes.

Thank you for getting this far! A couple of things before you go…

First, Londoners (especially South Londoners) - I am giving an in-person talk about Mrs Meredith and the Convict Laundries of South London at the Carnegie Library in Herne Hill on Tuesday 14 March, 6.30 for 7pm. Book here:

Second, for all those interested, my (non-fiction) published books are listed here: naomiclifford.com. For the record, I am currently working on a historical novel based on real events…

La rue à Londres is available at Gallica, the website of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (I am not aware of an English translation).

The review Les Amis de Jules Vallès devoted its No. 30 (Dec. 2000) to La rue à Londres.

The quote from John Sturrock: London Review of Books, Vol. 28, No. 3, 9 Feb. 2006.

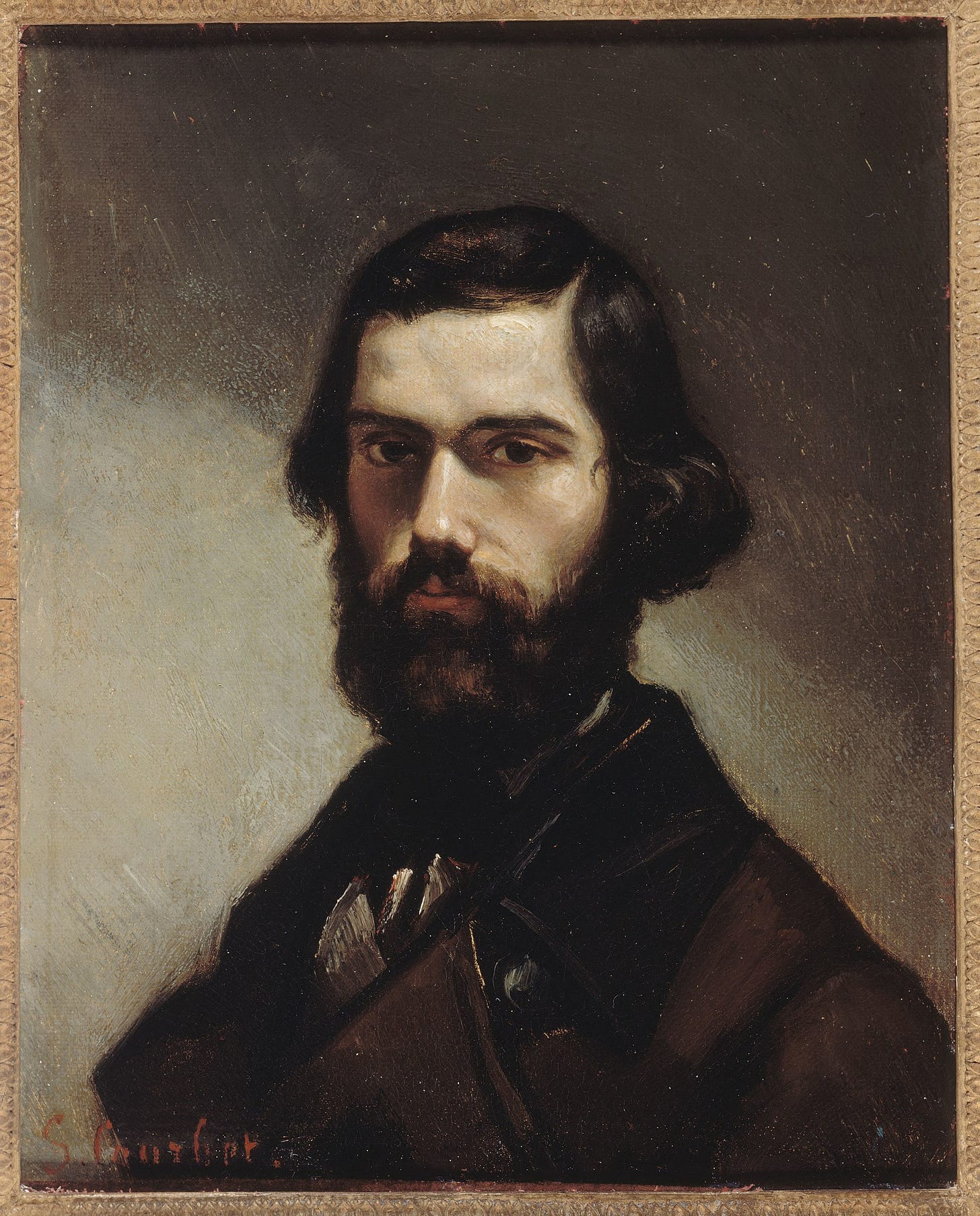

How interesting! Valles must have been well known on his circle to be painted by Courbet.