“Forward, the Light Brigade!”

Was there a man dismay’d?

Not tho’ the soldier knew

Some one had blunder’d:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

The Charge of the Light Brigade (2nd stanza), Alfred Lord Tennyson, December 1854

SOME OF YOU enjoyed my recent tour of the cheap end of Park Lane in London’s Mayfair, so for this post I have decided to head a couple of hundred metres north to one of the streets that run at right angles to the main drag of Park Lane.

The Third Earl of Lucan lived in a substantial town house in South Street (when he was in town that is — he also had Laleham Park, a country estate in Surrey, and his Irish estates at Castlebar). The house was destroyed in the Blitz.

When I say, ‘I am writing a novel featuring Lord Lucan’ the reaction is usually ‘Ohhhh! Him!’ Then I explain that he was not the dastardly nanny-murdering Seventh Earl but his great-great-grandfather George Bingham, the Third Earl, of Charge of the Light Brigade fame.

It is important (to me at least) to know that in 1872, the year the main action of my novel is set, Lord Lucan was maintaining three relationships. His estranged 62-year-old wife Anne Brudenell, the mother of his six legitimate children; his 32-year-old mistress Elizabeth Powell, who lived in a nice double-fronted villa with their two young children Lavinia and George two and a half miles away from South Street at 81 Maida Vale; and Julie Riel, a 25-year-old French actress, who lived with her mother and two servants at 13 Park Lane.

Aside: I am reminded of Mrs Merton famously asking the question, ‘What first, Debbie [Magee] attracted you to the millionaire Paul Daniels?’

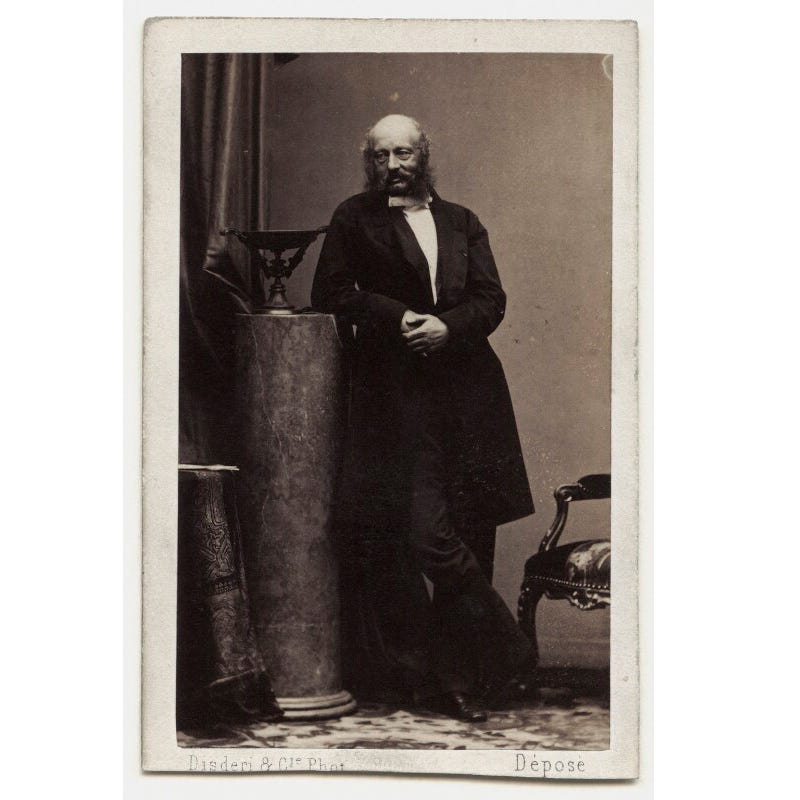

Here he is in 1863 in a photograph made by the famous photographer Disdéri in Paris. Lovely fella, ain’t he! Try to imagine him ten years on.

The historian Cecil Woodham Smith wrote in The Reason Why that Lucan had no common sense. Other words that have been used about him: vain, obdurate, harsh, stern, perfectionist, martinet, suspicious, temperamentally a loner, few close friends. He liked to throw his weight around with the junior ranks.

Difficult to like, I would say.

He was reviled on his estates in Castlebar, County Mayo, partly because he spent a lot of money converting them into large farms, which involved evicting families from their tenant farms and forcing them into workhouses in the towns or emigration. They called him The Exterminator.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography was not impressed:

In the parish of Ballinrobe alone he demolished over 300 cabins and evicted 2,000 people (1846–9). He then consolidated the holdings and leased them to wealthy ranchers. Chairman of the board of guardians of the Castlebar Poor Law union, he refused to pay his full Poor rate and insisted that the Castlebar workhouse should be closed at the height of the Famine. His heartless conduct was strongly criticised in parliament, but Lucan defended himself by claiming that he had invested heavily in his lands and that the Famine was proof that consolidation was in his tenants’ long-term interest. The execration he received in these years only aggravated his harshness, irascibility and self-righteousness.

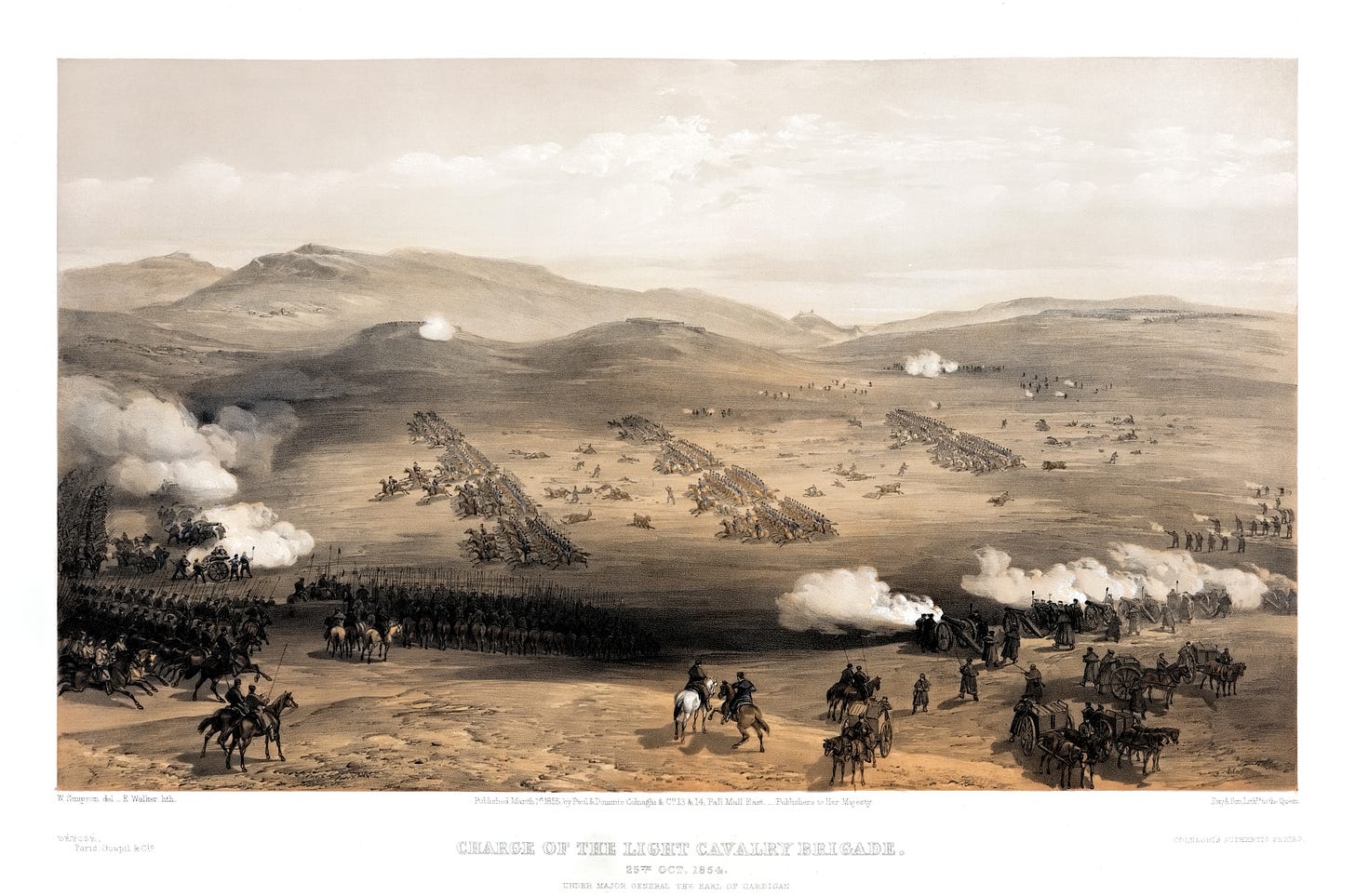

So, we come to the Charge of the Light Brigade. Google it at your leisure or watch the 1968 film starring Trevor Howard as Lord Cardigan (£3.49 on YouTube/Google/Apple). I am not a military historian or a military anything but my take is that he was rubbish at his Army job too.

Thank you, Royal Collection Trust, for this explanation of what was going on: as war approached between the allied nations of Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia against the Russian Empire, Lucan had overall command of the cavalry division. He was inexperienced in commanding in the field and unfortunately so were his two brigade leaders — Lord Cardigan of the Light Division (who was also Lucan’s brother-in-law — and unhelpfully they detested each other) and Sir James Scarlett of the Heavy Division.

On 25 October 1854 during the Battle of Balaklava Lord Raglan issued an order to Lord Lucan to capture guns previously taken by the Russians. The order was conveyed by Captain Nolan, and in turn Lord Cardigan was instructed to lead a charge towards the guns.

Miscommunications (it all hinged on the meaning of a handwritten note) sent Cardigan towards the wrong guns whilst under fire from three sides. Five regiments of Light Cavalry charged.

Result = very bad for the Light Brigade | Dead = 156 | Rank and file 129, trumpeters 4, sergeants 14, officers 9 | 122 wounded, unknown numbers taken prisoner and 335 horses killed in action, or destroyed afterwards.

Lucan, who was never again given an active command, expended a great deal of energy exonerating himself of blame for the bloodbath but he was known in the Cavalry ever after as Lord Look-On, pointing up the way he observed from on high as the Light Cavalry was destroyed.

Question: In the Crimea, did the notorious Lord Lucan, the non-hero of the war, cross paths with Florence Nightingale, the angelic ‘lady with the lamp’? I doubt it. Nightingale arrived at Scutari in Constantinople in late 1854, having been asked by her friend Secretary of War Sidney Herbert to organise a corps of nurses to tend to the sick and fallen soldiers in the Crimea. Not the sort of place Lucan would go,

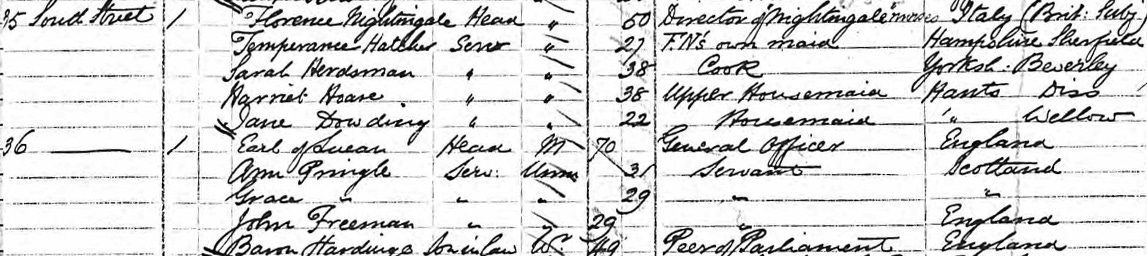

I do know that by 1871 the founder of modern British nursing and the notorious Lord Lucan were next-door neighbours in London.

Lucan, aged 71, lived with two female servants and a manservant, and his son-in-law (his daughter’s widower), Baron Hardinge. Florence Nightingale, then aged 51, employed four servants, a personal maid, a cook, and two housemaids.

Did Lucan and Nightingale nod to each other in the street? Did their servants gossip to each other about their employers? I would love to have been a fly on the wall.