Meet Eugène Appert, who photoshopped the Paris Commune

He was a pioneer of photomontage, but not necessarily in a good way

DEEP IN THE stacks archives at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France is a small fat photograph album, barely eleven and a half centimetres tall. It has been made for a specific purpose: to hold cartes de visite, the palm-sized photographic ‘calling cards’ that were popular in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

‘Commune de Paris 1871’ has been tooled in gold leaf on the red leather spine. Inside, held in place by linen tape, are sixty of these cartes illustrating the brief and doomed left-wing insurrection against the French government in the spring of 1871 which ended in a mess of fire and blood. Some are portraits depicting people, not just the prominent defeated Communards but also the so-called heroes of the conquering French Army. Others are staged tableaux illustrating atrocities alleged to have been committed by the Leftists or scenes, photographed after the fall of the Commune, of the ruined boulevards and burnt-out buildings. All are the work of Eugène Appert (1831-1890), a society photographer and enthusiastic early pioneer of the techniques of photomontage, who took upon himself an extraordinary project to photograph the Communards in prison and create notorious scenes from the history of the Commune.

The album in the BNF once belonged to Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, who was eleven years old when the Commune fell. Étienne grew up to be an artist and a collector of art. Perhaps, as a child, he was given the album by someone who recognised his early fascination for image and drama. Perhaps he selected the cartes himself and patiently fixed them in, or perhaps he acquired the album later in life, with the contents pre-loaded. The album gives us no clues.

This small book does has something to tell us that is relevant to the story of Marguerite Diblanc. Although women hardly feature in Étienne’s collection, Appert’s famous photomontage of dozens of Communard women in Chantiers prison is there (I’ll come to this in a minute). There is only one other depiction of a woman, and that is a smudgy vignette of ‘Marguerite Disblanc’ (she’s bottom left in the screenshot above). Did Étienne know who she was? And did he connect this image with newspaper reports in 1872 of Margaret Diblanc (correct spelling), a young Belgian cook who was hunted down in Paris by police days after her employer’s body was found in a house in London? Or did he assume that the woman in his album was a pétroleuse, one of a band of terrifying insurrectionist women who were rumoured to have taken their revenge by setting Paris alight in the dying days of the Commune? The same carte, held by the Musée de Carnavalet in Paris and many other archives, labels her as one.

The photograph of Marguerite is strangely flat and there is something unnatural about the pose, as if her body is turned one way and her head another. It’s only a matter of a few degrees, but disconcerting nevertheless. Her forehead is unusually shallow and her hair is plastered close to the scalp, making a plateau of the top of her head. Over her dark satin evening dress she wears a tawdry gauze blouse with cut-aways revealing the flesh on her shoulders, a style not typical of a domestic servant.

Appert had a history of using photomontage for political purposes. After the Commune fell, when thousands of its supporters were detained by the French government, he obtained a licence – at considerable expense – to visit the prisons to photograph them. Many of these desperate people leapt at the opportunity to be photographed and called on their relatives to bring in clean clothes for the purpose. They had been living in very difficult conditions and relished the chance to show that they were decent, respectable people. Some of the prisoners may have felt that if they were executed or exiled to the French colonies in the Pacific, as many were, their families would at least have something to remember them by.

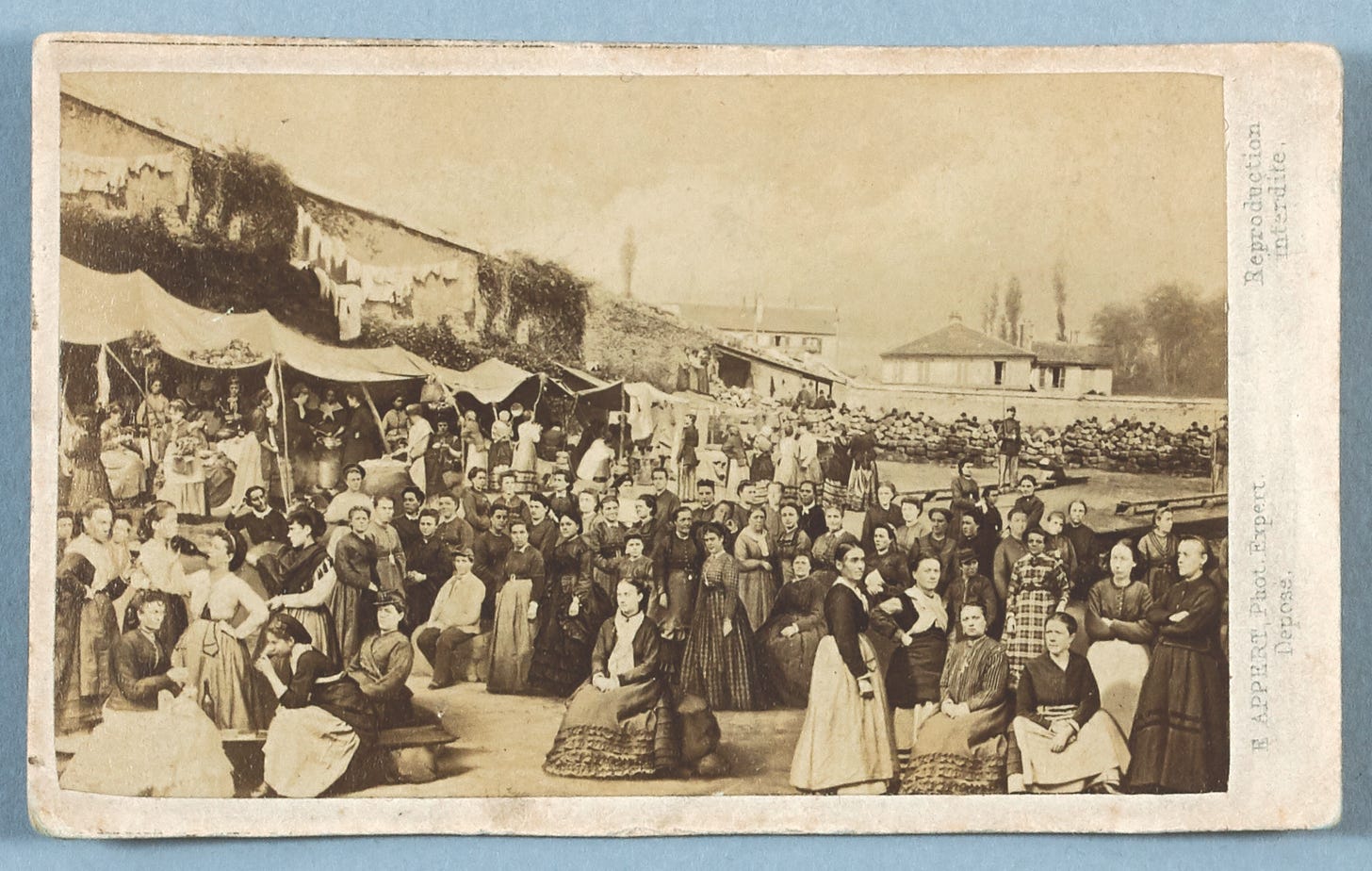

The process was simple. Appert arrived at the prison with an assistant. They set up their equipment in the yard, pinned up a plain sheet on the prison wall and placed a chair in front. As an inducement, Appert offered his subjects unlimited copies of the resulting cartes. The photographs, many of which have survived in collections and archives, show the prisoners in various poses. Some look defiant, others defeated. At Chantiers, the women’s prison in Versailles, a few are photographed in profile, drinking from beer bottles or smoking. One has her foot on the chair. Perhaps, for these women, the episode was a welcome diversion from the rigours of incarceration under a brutal and abusive regime, and Appert would have done nothing to encourage more decorous poses. For her photograph, Louise Michel, the defiant socialist activist and Communarde, sits armed crossed, unsmiling.

What Appert did not tell the prisoners was that he planned to use the images to create ‘fake news’ propaganda. In his studio, he photographed actors wearing the appropriate uniforms and clothes of both the protagonists and the victims of notorious atrocities that occurred during the Commune, and he also photographed the locations of the events. To make his photomontage, he cut out the bodies of the actors and stuck them on the photo of the location, adding the heads or upper bodies of the prisoners. Et voilà! He had fabricated an image that looked, to the unsophisticated viewer, as if it was a true record. The montages, which he marketed as ‘Atrocities of the Commune’, sold in their thousands. The women of the prison at Chantiers would have been bemused to see their heads on other people’s bodies. Although they are not shown taking part in crimes, the general impression of them is one of degeneracy.

For a while, Appert must have thought that his fortune was made. It was not. While his scenes sold like hotcakes, they were widely and illegally copied, and in December 1871, with most of the post-Commune trials over, in an effort to ‘move on’, the government banned the sale of images of the Commune. Appert’s investment went down the drain. By the time he manipulated the image Marguerite Diblanc, who had been convicted of murder in London, he was involved in an expensive lawsuit and deeply in debt. He must have thought he could profit, at least a little, from exploiting this woman’s notoriety.